por Harsh Mariwala

Resumen:

When the author launched what would become Marico as a division within his family’s business, Bombay Oil, it was with product innovation: Instead of selling edible oils in bulk to other businesses, it would sell in smaller, branded packages directly to consumers. Eventually the division became a separate entity, which is now one of India’s largest homegrown CPG companies. Its growth has depended on constant innovation—around not just products, packaging, and pricing but also supply chain, talent management, and business models. Over the past decade Marico has branched out into services with its Kaya skin-care spas, pioneered the use of premium hair oils, and added savory oats to Indian diets. Through the Marico Innovation Foundation, Mariwala also promotes innovative thinking outside the company, supporting small businesses and entrepreneurs in their efforts to scale up new ideas. The key to doing that well, he says, is to be ever curious about customer needs, to create a flat hierarchy that rewards risk-taking, to learn from every failure, and to constantly prototype, experiment, refine, and retest.

___

Marico, the Indian consumer-goods company I founded and still lead as chairman, was conceived around product innovation. I was a young man working at Bombay Oil Industries, the family firm that my father and grandfather had incorporated in 1948, which made and sold edible oils, oleo chemicals, and spice extracts in bulk. It was a commodity business with fluctuating margins and low growth, but I’d spent enough time analyzing our offerings and operations, traveling around India to observe consumer behavior across various regions, and talking to the end users of our products to see a hidden opportunity: We could do better by selling our oils in smaller branded units. I knew how traditional Indian businesses were run, but having visited the United States, I could see different market dynamics bubbling up. The task was clear: We should launch a small consumer-products division within the parent company.

Our focus would be to create value by nurturing innovation, finding additional paths to growth, and capturing previously untapped markets. There is a thrill in launching something new and watching it gain momentum; everyone involved in that fledgling division felt it, especially me. By 1990 our business was large enough to spin off under its own corporate brand—Marico. Over the next decade it became a household name.

I’ve always insisted that we continue to come up with new ideas, experiment with and iterate on them, and bring the best offerings to market. That commitment extends not just to new products, packaging, and marketing but also to our supply chain and talent management practices and our business model. Success requires not just leveraging your strengths but also taking risks, overcoming challenges, learning from failure, evolving your vision, and sometimes reinventing yourself. That’s true for both organizations and individuals.

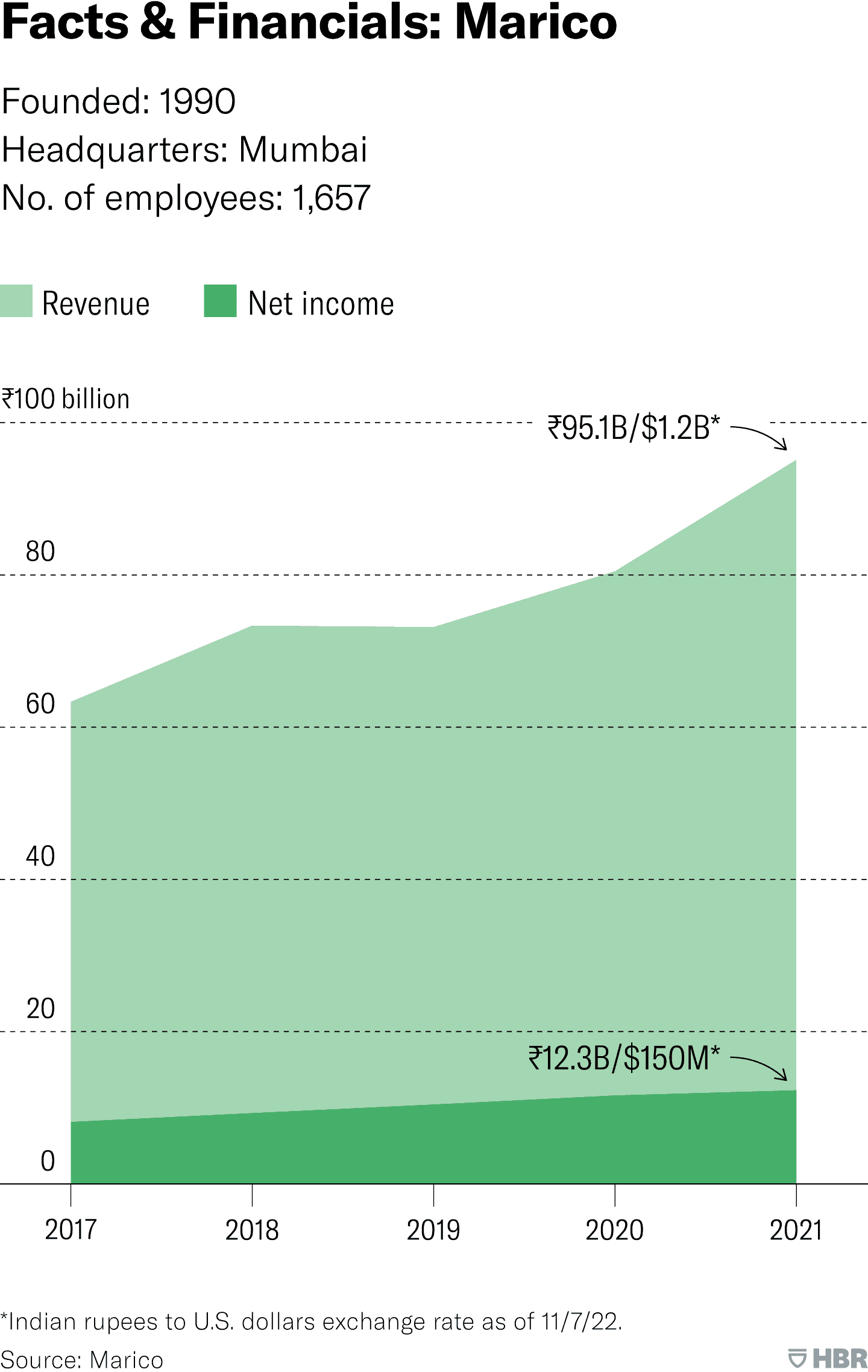

This ethos helped me transform a small family-firm division with early annual sales of about $61,000 into an independent, professionally run, and publicly traded entity with dozens of leading brands and a market capitalization of more than $8 billion. More important, I believe I’ve created an organization where innovation will carry on long after I’ve retired. I’ve also tried to inspire, recognize, and support fellow entrepreneurs and business owners around India through the initiatives and programs of the Marico Innovation Foundation, which I started in 2003.

Family Origins

The roots of our family business lie in the early days of Indian spice trading. My grandfather and great-granduncle specialized in ginger, turmeric, copra, and pepper shipped from Kerala to traders from Delhi, Calcutta, Amritsar, and Karachi. They opened a spice shop and a processing plant, and soon both earned the nickname “Pepper Man”— Mari-Wala in Gujarati—which became our family surname.

After India declared its independence from Britain, in 1947, my grandfather began exporting to Europe. My father then made a case for pushing further into manufacturing, starting with a small mill to convert copra into coconut oil. Next he set up a crushing plant, a refinery for edible oil, an oleochemicals plant, and a spice extraction unit, enabling the conversion of raw materials into finished products. He and his father incorporated Bombay Oil Industries and developed a reputation for quality products. By 1965 they had two brands—Parachute coconut oil and Saffola refined safflower oil—but most of their offerings remained unbranded, and everything was sold in tanks, barrels, and 15-kilogram containers.

I grew up watching my elders at work and was expected to follow in their footsteps. After studying accounting and economics at Sydenham College, I applied to the top management schools in India but wasn’t admitted. I then asked my father if I could apply to U.S. and European MBA programs, but he said no, asking me to take a short trip abroad instead and then come back to join Bombay Oil. I was disappointed, but in hindsight his directive was a blessing in disguise.

On my travels overseas I discovered shops and malls laden with consumer brands in every category. Store layouts were well organized, packages were eye-catching, and advertising was seductive. Compared with the limited choices in the Indian market, this was a revelation. Returning to Bombay Oil in 1971, I found myself an employee with no real responsibilities, department, or supervision. It sounds like nepotism—and it was—but I used my freedom wisely. I visited our factories, tagged along with managers, spoke with office staffers in various departments, listened in on and attended sales calls, and talked directly with buyers about quality, pricing, service, delivery schedules, and complaints. I studied competitors’ strengths and weaknesses, pored over our finances, and went not just to our key markets but also to those we weren’t present in, visiting distributors and analyzing dynamics across the country.

I took management-training courses, too, to learn HR, accounting, and the like, but it was my on-the-ground research that gave me the most useful education—and eventually emboldened me to suggest changes at Bombay Oil. Those included factory automation, modern finance and sales systems, new HR processes, and eventually a business model shift—from bulk sales to consumer packaged goods—that put the company and my career on an entirely different trajectory.

Building Our Consumer Brands

Our two existing brands, Parachute and Saffola, were respected. Retailers, to which we supplied our 15-kilogram tins, would often dispense smaller measures of “loose” oil at a premium to customers who came in with empty bottles to fill. We could capture that margin ourselves and grow market share by selling our oils in more user-friendly sizes. We introduced two- and one-kilogram packaging, followed by 500-, 200-, and 100-milliliter tins. We recruited a sales manager from Hindustan Lever (a subsidiary of Unilever) and hired sales reps to tour the country promoting those new sizes to distributors and shop owners. We also ramped up our advertising and became more creative, launching the first-ever ad campaign for Parachute and promoting Saffola by touting the cholesterol-lowering properties of safflower oil. No edible-oil brand in India had focused on health before. We circulated literature on heart care, enlisted doctors, organized medical conferences, and produced books of healthful recipes, enriching the lives of Indian consumers while promoting our products. Our smaller packs were already winning over many consumers, but I thought that even stronger differentiation would dramatically increase our market share.

That led to our next packaging innovation. Our tin containers weren’t very attractive or easy to use: You had to puncture the tin or cut open foil to get the oil out. I realized that plastic receptacles with spouts would be more aesthetically pleasing and make pouring easier. They would also cost less, allowing us to lower our prices while accruing extra profits to further invest in the brand. Although consumer research confirmed a preference for plastic over tins, distributors and shop owners were opposed, in part because a few years earlier another coconut oil producer had tried square plastic bottles, which leaked, attracting rats that chewed through the corners. Our solution? Rounded containers, with no edges to leak or to gnaw at. We even tested the new design by putting oil-filled bottles in cages with rodents for two days with a camera trained on them. Nothing happened! Our sales team shared the photographic evidence in the field, assured retailers that they would be reimbursed for any leaks or damage, and explained the potential for lower prices and more advertising. Soon our plastic bottles were widely accepted. However, we didn’t stop iterating: When we realized that the oil would become viscous in bottles during winter months, we redesigned the bottles to have a wider mouth that allowed for scooping as well as pouring. Moving region by region, showing positive results in each before going on to the next, our CPG business built national distribution in less than 10 years.

The Next Chapter

Led by soaring sales of Parachute, which pushed its share of the coconut oil market from 15% to 45%, Bombay Oil’s turnover increased fivefold during the 1980s. I knew early on that I would need to engage professionals to grow the consumer-products division to compete with multinationals like Unilever, Nestlé, and Procter & Gamble. However, although our division could afford those hires, I was met with stiff resistance from family members who led other parts of the company. At the same time, I was frustrated by a lack of systems and processes to accurately track costs, revenues, and profits across our various businesses. Accountability was lacking, and we continued to be a hierarchy based on age and seniority, not a meritocracy.

I realized we needed drastic change, so I initiated a conversation with some younger cousins at Bombay Oil who also felt that their business aspirations were being constrained. We agreed that the best way forward would be to carve out each of Bombay Oil’s businesses as an independent company, so we set out to bring the seniors on board. After much time, effort, and deliberation, the plan was approved—a watershed moment of winning consent and consensus through dialogue, perseverance, and belief in my vision. Everyone involved felt inspired to forge ahead to the future. I decided to name the newly independent consumer-products company Marico, a play on my name.

We knew that to capitalize on our success to that point and recoup some of the costs of spinning off from Bombay Oil, we had to quickly distinguish Marico as not just a leading CPG supplier but also an employer of formidable talent. With limited resources, we again had to innovate. I asked our marketing agency to develop a short but striking ad campaign to announce our arrival. It had three parts that mimicked news articles. The first was headlined “200 Employees Walk Out of Bombay Oil” and went on to reveal that they were doing so to launch Marico. The second, “Mass Killer Nabbed,” detailed Saffola’s contribution (according to the medical data then available) to lowering the risk of heart disease. And the third, “Lalitaji Boycotts Coconut Oil,” explained why a fictional cost- and quality-conscious housewife famous across India rejected any coconut oil other than Parachute. Those ads created buzz among Indian consumers and appealed to up-and-coming young managers. We were a new, exciting company willing to try out-of-the-box ideas.

I was also clear about the organization I wanted: one with decentralized decision-making and competent professionals filling the ranks from the top team to the front lines. I knew that my first Marico hire had to be an HR leader who would add credibility and value to our hiring strategy. With the help of that new CHRO, Jeswant Nair, who shared my desire to build an employer brand around empowering people to innovate, we quickly recruited a strong team of experts who knew much more than I did about their respective fields. I told them all, from executives to laborers, to call me Harsh.

Over the next few years we further developed our corporate brand and culture around three Ps: people, products, and profits. We knew that people—team members, customers, and business partners—were our greatest strength. Together we would make products of superior quality. Our profits would measure how well we satisfied the needs of Indian households and be reinvested in the business to improve our existing products, create new ones, and keep our people engaged. It was a virtuous circle. Through that lens we identified necessary and long-overdue improvements, such as significant upgrades for our factories and refineries, along with better management practices—perhaps ahead of their time—which included abandoning attendance requirements and simply making people accountable for achieving the desired results.

Most important, we encouraged new ideas, experimentation, calculated risk-taking, and the questioning of conventional wisdom. Everyone knew that mistakes were acceptable if they provided lessons that would make the next initiative more likely to succeed. Experimenting businesses never lose, only learn. So during the early 1990s we made some unexpected moves. Foremost among them was opening a state-of-the-art factory in Kerala, the source of our coconut oil. It offered lower-cost land and highly educated workers, but the state was viewed as industry-unfriendly because its labor unions were so powerful. Again, we succeeded because we innovated, creating a facility that prioritized worker and community interests with fair wages and ample training and development. Over a decade the project saw a return that was more than 10 times its cost and became a model for better production.

All the while, our product and packaging innovation continued apace. We launched Marico’s Hair & Care, a premium, lightly perfumed hair oil, and Revive, a cold-water-soluble instant fabric starch. To thwart Parachute counterfeiters, we introduced a pilfer-proof cap. For the Saffola brand we created a heart-shaped, easy-pour container; new blends; low-sodium table salt; and a high-fiber wheat flour mix.

By 1996 Marico’s sales had quadrupled and profits had doubled. My uncle Kishore and I negotiated with our other family members to buy out their interests within 18 months at a valuation determined by a third party. Ultimately we had to get creative about financing it and decided on an initial public offering. Some doubted that a homegrown Indian company could attract investors in an era when our market was dominated by multinational CPG companies. But we did. In a bearish market, the listing was well priced and oversubscribed. My uncle and I sold some ownership but retained 65% of it and raised much-needed capital.

New Frontiers

To make the leap from a CPG upstart in the 1980s and 1990s to a major industry player in the 2000s and beyond, we needed even more innovation. Working with the management luminary Ram Charan, we began to earmark 20% of annual profits for a strategic fund to develop new growth engines. That was how we would keep the pipeline of new products, brands, and business ventures full. One success from that period was a huge expansion of our hair oil lines into pre- and post-wash offerings with varying ingredients—available in a variety of sizes including single-use sachets—which we promoted with thoughtful advertising around special occasions such as Holi and Diwali. By 2019 Marico had a 25% share of that fast-growing category, and we soon leveraged our brands to expand into other grooming products such as gels, creams, and serums.

Working with the Saffola brand, we tried baked snacks made from extruded high-fiber grains but quickly learned that customers expected indulgence foods to first and foremost be tasty—another failure-born insight, which we carried into a more successful brand extension: Saffola Oats. Starting with the plain oats popularized by U.S. brands like Kellogg’s and Quaker, we soon gained a 15% market share. But the real innovation was in flavor. We knew that Indian consumers tend to prefer a savory breakfast, so we developed offerings to suit various regional tastes—tomato oats, pongal oats, masala oats, lemon and pepper oats—and found a new way of introducing them: in vending machines in airports, offices, gyms, and hospitals. They were a hit, and Saffola now has an 80% share of the savory oats market.

Another relatively recent triumph came from innovation in our business model: selling services as well as products. Hair-removal clinics had become hugely popular in the United States and the UK, and we thought Indian consumers would flock to them. But we didn’t want to get into a business that could easily be copied and commoditized. So we began researching and prototyping an upscale, high-tech clinic that would offer an array of skin-care treatments. We bought equipment, hired staffers, and set up an experimental version in our Mumbai headquarters, asking volunteers to come in and give the services a try. Thus a new Marico subsidiary, Kaya, was born, and we were in the beauty business. Within a year we opened three clinics in Mumbai and three in Delhi. Soon we were elsewhere in India and in the Middle East. In an interesting twist, Kaya later became a platform for launching a range of skin-care products, retailed through the clinics and other channels. We now have 95 clinics in 31 cities in India and the Middle East and 62 Kaya products, generating annual revenues of 4.2 billion rupees ($51.3 million).

Finally, we have creatively expanded our business into new geographies, targeting Indians in the Middle East and like-minded consumers in Bangladesh with established Marico products while acquiring brands in other emerging Asian and African markets. Our international revenues now account for nearly a quarter of Marico’s total.

The Way Forward

In 2014 I handed the reins of Marico to an able successor (and not a family member), Saugata Gupta. Since then he has driven innovation at the company, though I continue to advise and guide it as chairman. Today I spend most of my time trying to spread our ethos in the Indian business world through the Marico Innovation Foundation (MIF) and the Ascent Foundation; initiatives including research and intervention programs; our well-recognized biannual event, Innovation for India Awards, to identify and recognize breakthrough innovators; and the Scale-Up program, which provides pro bono support to entrepreneurs, including access to and mentorship from networks of industry leaders who teach not just what to do but also how to do it. Over the past 18 years MIF’s mission has been to unearth, nurture, and help scale up game-changing innovations that enhance economic and social value in India, and we’ve been associated with more than 100 projects across diverse sectors.

When young people ask me what I learned in my five decades of building and leading Marico, my first response is “to focus.” You should know your individual and organizational strengths and build on them to achieve depth and excellence. At the same time, you should be aware of and open to what’s happening around you. There are always indicators of shifting mindsets and opportunities. If you remain alert to them and take calculated risks at the right time, you can spark growth. And even if you don’t achieve the outcome you desire, you will learn valuable lessons in the process.

A key component of leadership success is understanding that your role is not just to make decisions but also to build an organizational culture that allows for the free flow of ideas and experimentation. Innovation can come from anywhere—but only if you are listening, leveling the playing field, and bringing people together in a shared purpose.

Above all, it’s important to embrace innovation in every aspect of the organization. It doesn’t always involve a new product or service; sometimes it’s about solving a process bottleneck, developing a more astute way to collect consumer insights, or building a stronger, more diverse team. When you broaden the lens on innovation, you multiply your organization’s chances of success. That’s the only way to make quantum leaps in career, corporate, social, or economic growth.